The Phenomenology of the Self

Copyright © 2010 William Meacham. Permission to reproduce is granted provided the work is reproduced in its entirety, including this notice. Contact the author at http://www.bmeacham.com.

Click here for the PDF version, better for printing and reading offline.

In this chapter I summarize what I have found to be the case with regard to the structure and composition of the human self (note – with a lower-case s) as experienced from the inside, from the phenomenological point of view. This is only a summary. My doctoral dissertation, A Phenomenology of the Self, contains much more detail.

Looking at the phenomenologically-observable elements and structure of the self is analogous to looking at the chemical and molecular structure of the human body. They are low-level structures that can elucidate the mechanism by which things happen, but higher explanatory levels are more interesting: levels such as motivation, reason, goal-seeking, strategies for dealing with emotions, functions of emotions as helping or hindering attainment of goals, etc.

What is most interesting about the phenomenology of the self is the absence of the Self (with an upper-case s). I treat this subject in other chapters.

The motivation for this chapter is the ancient Greek advice “know thyself.” Philosophy is the pursuit of wisdom, the craft of leading a good life, and one cannot be wise without knowing who and what one is. We all, pre-reflectively, think we know who we are to a greater or lesser extent, but when we really think about it, it is not all that obvious. Some careful investigation is necessary, over some period of time. This chapter contains the results of my own investigation.

This chapter contains a sort of inventory of the building blocks of experience, as observed from the first-person, phenomenological point of view. This section describes that method.

The term “phenomenology” denotes a method of study: biasless reflective examination of experience. (It can also refer to the thing studied, as the term “geology” refers both to the study of physical features of the earth and the physical features themselves in a specific area, as in “the geography of the Texas Hill Country”. It is in the latter sense that I title this chapter “the Phenomenology of the Self”.)

Phenomenology as a method entails careful observation of one’s own experience. In order to be extremely careful – careful enough to attain knowledge and not just opinion – one attempts to take nothing for granted, that is, one attempts to disregard all theories and doctrines of what experience is and of what is experienced. One simply pays attention to the experiencing, both as it happens and as one remembers it.

I have described my use of the term “experience” in the chapter on “Consciousness and Experience. Now I turn to the meaning of “biasless reflective examination,” dealing first with reflection and then with lack of bias.

Phenomenological reflection is a species of ordinary reflection. “To reflect” means, in a general way, to think; but to reflect is more than to think. To reflect is to take a mental step backwards, to consider something in its broader context, to see how it is related to other things, what its nature and place in the world are. If, in the straightforward course of one’s daily life, one gets angry with someone and speaks sharply to that person, one has an unreflective experience of anger. If one stops to consider why one got angry, what effect the anger had on that person and on oneself, etc., then one is reflecting on one’s anger. In order to reflect, one must suspend one’s interest, stand back and take a neutral attitude, and try to think about one’s more clearly and in a broader context. Reflection requires detachment and widens the scope of inquiry. The process is the same whether the object is an aspect of oneself or of one’s world.

Phenomenological reflection is no different. The difference between naively and straightforwardly experiencing something, say seeing a tree, and phenomenologically reflecting on that seeing is as follows: In the naïve experience one’s attention is directed toward the tree. Certain interpretations – what Husserl calls “noeses” and Peirce call “perceptual judgments” – are present, but only operatively, in the background or “margin”1– interpretations such as that this object is a tree, that it is an Object2, perceivable by everyone, that if one walks around it one will see the other side, etc. If one reflects on this experience phenomenologically, one can make these operative interpretations thematic; that is, one can attentively notice the operative interpretations, as well as the tree subjectively experienced through them. Thus one apprehends the tree in a broader context, the context of the rest of one’s experience of the tree. “Reflexion,” says Husserl, referring specifically to phenomenological reflection, “is an expression for acts in which the stream of experience (Erlebnis), with all its manifold events (phases of experience, intentionalities) can be grasped and analyzed . . . .”3 We’ll see later what “intentionality” means. Here, note that phenomenological reflection on an experience reveals the whole experience, not just the focal object of the experience. A clearer statement is found in Cartesian Meditations: “. . . reflection makes an object out of what was previously a subjective process but not objective.”4 Thus, what was only operative, only in the background, in the original, un-reflected-upon experience becomes available for attentive inspection when one reflects upon the experience – and this background includes not only operative interpretations (noeses or perceptual judgments) but also subjective reactions to the focal object, such as interest or disgust or aesthetic delight, etc., as well as extraneous elements that may or may not be present, such as idly thinking about something else.

Although most instances of phenomenological reflection on experience are recollective, i.e., the reflected-upon experience is present in the mode, “remembering it,” this need not be the case. One can pay attention to one’s experience while it is happening, thematically noting operative interpretations as well as the focal object and concomitant subjective feelings. Husserl speaks of “immanent perceiving reflexion,” that is, reflection that has as its object an experience as it is going on.5

Of course, when one reflectively considers an experience, whether in the modes, “remembering it,” or “thinking about it,” or immediately apprehending it as it is happening, the experience reflected upon is not the same as the experience of reflecting on it. The experience reflected upon is the intentional object – only one aspect – of the reflecting experience. Says Husserl, “. . . reflexions upon experiences [are] themselves experiences of which we are unreflectively aware.”6

The first two characteristics of phenomenology are that it is directed at experience and that it is reflective. The third characteristic is that it is to be biasless. It is the reflecting experience – the process of being conscious of the reflected-upon experience and actively trying to notice all the aspects of it – that is to be free from bias. It is to be free from bias in order that the biases inherent in the reflected-upon experience can be clearly “seen” (observed, apprehended, grasped, noticed in any mode of experience). Indeed, in the natural attitude, naively living in the taken-for-granted lifeworld,7 we normally have a strong bias against becoming conscious that we are biased – too much questioning of our taken-for-granted assumptions is regarded as threatening or subversive.

The elimination of biases in the reflecting experience so that the reflected-upon experience can be “seen” in its entirety is what Husserl means by “bracketing” the natural attitude; it is his epoché, or abstention from questions of existence and non-existence.8 One of the most fundamental presuppositions of the natural attitude is the assumption that the Objective world has factual, spatio-temporal existence; phenomenological reflection reveals this assumption for what it is, a complex set of operative noeses functioning to interpret one’s sensations as perceptions of a really existing world. In the Cartesian Meditations, Husserl speaks of “absolute freedom from prejudice.”9 A clearer statement appears in The Paris Lectures: “Phenomenological experience as reflection must avoid any interpretive constructions. Its descriptions must reflect accurately the concrete contents of experience, precisely as these are experienced.”10 In practice, as one observes or remembers one’s experience, one notices that interpretations are there, but one does not get drawn into the world or thought chain of the interpretation; one avoids getting caught up in their story.

Freedom from bias is an ideal toward which the phenomenologist strives, but it is not something accomplished easily or all at once. One must reflectively apprehend a typical state of affairs or mode of experience again and again to be sure one has not missed anything and has made thematic (paid attention to) all the operative interpretive elements. One should engage in dialogue with other phenomenologists as a further check; this chapter is an attempt to do that. Eventually there comes a time when one has made thematic all that is present in a moment of experience or a certain type of experience, and – try as one might – one cannot find anything more that one has left out, nor anything that one has “read in” that is not in fact there.

Corresponding to the different modes of being reflectively conscious of an experience, the injunction to be without bias, to observe without presuppositions, prejudices, preconceived notions, ungrounded concepts and theories, etc., takes different forms.

When one thinks about experience – experience in general or a particular type of experience – one must be careful not to try to interpret or explain what one “sees” in terms of concepts and theories whose meaning and truth one has not subjected to thorough criticism. It is illegitimate, for instance, to interpret the process of experience as a function of brain-processes or of social interaction or of hypothetical psychological entities such as libido, id, ego, etc., because none of these categories correspond to what is strictly reflectively observed to be elements in the experience reflected upon. After one has attained a clear idea of what is inherent in the different modes of experience, one may go on to incorporate one’s findings in a larger theory and use concepts derived from other areas of inquiry, as I do in other chapters of this work, but not before the proper groundwork has been laid through careful examination of what is present in experience itself.

The injunction to observe without presuppositions acquires more force in the case of being remembering a particular experience. It is all too easy to “read in” elements that one thinks ought to be there because some theory or doctrine says so, but which are not in fact there. Moreover, one must be careful not to overlook elements that one doesn’t expect.

This is particularly important in being reflectively conscious of an experience while it is going on. It was only after many attempts reflectively to grasp my experience in its concreteness that I, the author of this essay, began to be able to be conscious of the specifically noetic elements in experience, the nearly subliminal interpretations and perceptual judgments that let me know that a particular configuration of shape, color, texture, etc., for instance, is my computer, an enduring Object, usable for specific purposes and with a certain sentimental value. The beginner in phenomenology should not be too easily discouraged at the outset if he or she does not find the wealth of detail that Husserl and the other phenomenologists assert to be present in experience. Our habit of overlooking the subjective and noetic elements in experience is too ingrained to be easily or quickly overcome.

Perhaps it would be helpful for me to explain how I myself practice phenomenology. Most of my own reflective analysis of experience occurs in situations in which I almost spontaneously disengage myself from an experience while it is going on and start to notice the different operative elements. I then spend some time “playing it back,” as it were, actively retaining it, recalling it and recollectively living through it again (often several times), now with enough distance explicitly to note features originally present only marginally or implicitly (operatively). I actively observe and pay attention to the experience, first in the mode, “ observing it itself,” and then in the mode, “retaining it” or “remembering it.” While I am doing this, I am making an effort to form a clear idea or concept of what I “see.” The beginning stages of doing phenomenology are devoted merely to sorting the various elements in experience into types; such as sensations, noeses, emotions, thoughts or ideas, bodily feelings, etc. Later, after I have gained some idea of what sorts of objects are present in each mode of experience, I can begin to “see” functional interrelationships between them. The sorting into types is based on what can be reflectively observed to be present in any single moment of experience, as if I were taking a snapshot of it and sorting out what I “see.” The various functions of each of the types of elements can only be “seen” over a period of time, because it takes some time for the functions to be performed – it is easier, for instance, to be conscious that there are noetic elements functioning to interpret my sensations if I notice that I take a series of changing sensations to be perceptions of an enduring Object than if I reflectively apprehend only one perspectival profile of the Object. Similarly, the functional interrelationships between the various aspects of my experience are much more easily noted over a period of time than in a single moment of experience. Of course, the apprehension of function aids the sorting into types. It is chiefly by virtue of function that noeses, for instance, are distinguished from mere nearly-subliminal idle thoughts.

Note that it is not necessarily the case that one must put all ideas out of one’s mind in order reflectively to apprehend an experience phenomenologically. What one must do is to put out of play all preconceived notions that one has not “seen” to be true, but inherent in the process of doing phenomenology is the attempt actively to form ideas of what is clearly “seen” in the reflected-upon experiences. Doing phenomenology has been likened to constructing maps of a new territory.11 Clearly, one must not depend on maps that someone else has made and of whose truth one is not sure (although one can certainly examine one’s experience in order to “see” whether those maps are correct). What one does instead is to form one’s own maps, based on what one observes to be the case. But once one has a map of one’s own, one may refer to it in order to get one’s bearings when reflectively examining a new experience. Indeed, one’s own maps are an invaluable aid to being clearly conscious of what is present in the reflected-upon experience. Whitehead has asserted that all being conscious is a matter of being conscious of something along with something else that contrasts with it, specifically that conscious perception always involves the contrast between the given (sensation) and the conceptual.12 I think he overstates the case; being conscious can also occur when there is a contrast merely between different things in the external world (in the sensory field that has the sense “Objective world”). But it is true that having an idea of what one has found in previous examinations of experience aids one in “seeing” what is present in an experience that one is currently reflecting upon.

Despite the stylistic necessity to capitalize the term in the heading for this section, in this section I list the phenomenologically-observable elements and structure of the self with a lower-case s, the human being as viewed from the inside.

The title of this chapter, “The Phenomenology of the Self,” seems to imply that there is one correct phenomenological description that is true of all human selves. That’s a strong claim, one that I am not quite making. I suppose I could have called this “The Phenomenology of a Self,” but I am fairly confident that my description is not merely idiosyncratic, because it seems to agree with observations made by many others, including Husserl, James, and Peirce, to mention only a few. (I say “seems” because language describing private aspects of experience is not nearly so precise and agreed-upon as the language used in the objective sciences. For instance, from context I gather that “operative interpretation,” “noesis” and “perceptual judgment” mean roughly the same thing.) I do not claim my description to be true of all humans with absolute certainty. What I am certain of is that what follows is what I have observed to be true of my experience. I invite you, the reader, to examine your experience and see if it is true of yours.

The main categories of elements found in experience are thought, feeling and action. These are all private, meaning only each of us individually can experience our own thoughts and feelings and perform our actions; others can experience and perform theirs, but not ours. (Phenomenologically we say that thoughts, feelings and actions have the sense “private,” or “my own.”) Hence we can say that all of these are components of the self because they appear in experience only to the one who is experiencing. In other words, the structural elements by which we perceive and interact with all objects, both the self and the not-self, I consider to be part of the self because of their private nature.

In any single moment of experience, one can find the following main classes of elements:

In any single moment of experience, the effect of the types of elements of the self can only be measured in terms of intensity; the more intense the element, the more effect it has on oneself.

Considering experience as it occurs through the passage of time, the types of elements listed above appear as the following:

The effect of these types of elements is measured by intensity, duration and frequency. The more intense an element is, the longer it persists and the more often it recurs, the more fully it is an element of oneself.

Thoughts and concepts, whether the result of deliberate thinking or not, may be present in any single moment of experience verbally or pictorially or in other sense-modes. Their character as being immediately present in experience I call their “material aspect” or “material quality.” If they are present with enough intensity to be attentively focused on and noted, they are fully verbal (words, phrases, sentences, etc., running through one’s mind) or visual (detailed pictures or gestaltlich outlines), etc. If they are present only vaguely and obscurely, I call them “preverbal,” “previsual,” etc., indicating that were one to focus one’s attention on them and bring them to mind more clearly, they would be fully verbal, visual, etc.

One’s thoughts are not merely subjective objects running through one’s mind. They refer to some state of affairs other than what is strictly present in experience, something beyond themselves; in short, thoughts are thoughts of something else. This aspect of thoughts is their “intentional aspect,” and that which they are thoughts of is their “intentional objects.” (This philosophical use of the term “intention” is different from everyday usage. It is derived from a Latin phrase meaning to aim at, and does not mean one’s determination to do something.) When one thinks of one’s car, for instance, and thinks that it is in the driveway, it is not simply the case that one has some mental object – the words, perhaps, “My car is in the driveway,” or a picture of it in the driveway. In addition, one knows that one is thinking of something other than what is immediately present to the mind, namely the car itself in the driveway, and one need only go look out the window to verify or falsify the thought.

A thought that has a relatively clear intentional object I call a “concept.” “Car,” “self,” “neutron,” “premises,” “run,” “perceive,” etc., are all concepts. Mental states of affairs, such as idle noises or visual shapes, etc., which do not have clear intentional objects may be loosely called “thoughts” but they are not concepts. The intentional aspect of concepts, their reference to intentional objects, is found in their fringe, that obscure mass of feeling that is not clearly focused on and which surrounds the clearly intuited core, the “free water that flows round” what is focally apprehended, as James poetically puts it.13 The fringe is composed of links or associations with a large number of objects, including other concepts suggested by the focal concept such as connotations, steps in reasoning, etc.; concepts of the surroundings or context of the intentional object; memories and anticipations of direct acquaintance with the object; typical knowledge of the intentional object, what it is, what it is good for, etc.; “recipes,” so to speak, for typical action relating to it, which I call latent action-schemata; and incipient impulsions to action. In any single moment of experience the fringe is difficult to “see” exactly because it is the fringe, what is not focally apprehended. It, or at least its effects, becomes more clear as one lets the incipient associational tendencies become actualized, as one thinks more about the intentional object, for instance, or about its context, or as one performs some action that brings one to direct experience of it. The intentional aspect of concepts consists in that they orient one to action regarding their intentional objects, either to thinking more about the intentional objects or to actually doing something with them.

The intentional aspect of concepts is also their function. The world as one experiences it is in constant flux; even stable and enduring objects such as rocks, trees, etc., are experienced by means of a changing series of perceptions of them, as one walks past or around them, touches them, etc. But concepts are relatively unchanging and stable. One’s concept of the typical characteristics of trees does not change, even though one’s direct experience of trees does. Concepts have, metaphorically, the same relation to their intentional objects as does a map to the territory it represents. If one has a map one can orient oneself and get around in a city or territory. As James says:

All our conceptions are what the Germans call Denkmittel, means by which handle facts by thinking them. Experience merely as such doesn’t come ticketed and labeled, we have first to discover what it is. . . . What we usually do is first to frame some system of concepts mentally classified, serialized, or connected in some intellectual way, and then use this as a tally by which we ‘keep tab’ on the impressions that present themselves. When each is referred to some possible place in the conceptual system, it is thereby ‘understood.’14

When one understands something, one knows what to do with it and is enabled to perform actions appropriate to it. Thus the function of one’s concepts – strictly speaking I should say one’s beliefs – is to orient one to action regarding their intentional objects.

Beliefs are concepts or judgments which one takes to be true. I follow Peirce in distinguishing belief from its opposite, doubt (not disbelief; disbelief in something is belief in its contrary), in three ways. First, believing feels differently from doubting. Second, there is a practical difference in that one is prepared to act on what one believes, but not on what one doubts. Third, there is another practical difference in that when one doubts (or simply is curious – at any rate when one knows or suspects that one does not know something) one is impelled to inquiry, the object of which is to attain belief and alleviate doubt. As Peirce says, “Belief does not make us act at once, but puts us into such a condition that we shall behave in a certain way, when the occasion arises. Doubt has not the least effect of this sort, but stimulates us to action until it is destroyed.”15

It is clear that what one believes is an integral element of oneself, because the system of one’s beliefs has a constant effect on everything that one does. We can distinguish more and less integral beliefs; fundamental beliefs that influence all or most of what one does are more fully oneself than mere knowledge, for instance, of where the mailbox is, knowledge which affects one’s life only intermittently and superficially.

The way we think of the world and what we believe to be true of it are highly influential factors in our perception of the world. One’s beliefs are present in one’s experience not only when one is clearly thinking of something, but every time one perceives something (or imagines it or remembers it, etc.) and recognizes what it is. There is an element in experience which Husserl calls “noesis” or “the noetic,”16 the interpretational, judgment-like fringe that surrounds or is present in experience with sensation and which functions such that one experiences an orderly and coherent world of discrete Objects, people, events, concepts, institutions, etc., instead of a chaotic flux. Noeses are in the fringe of experience, so they are not easily reflectively “seen” and are generally entirely overlooked in the course of one’s unreflective daily experience.

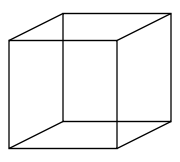

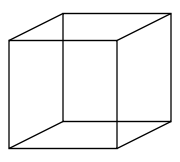

Here is an example of noesis or perceptual judgment: Consider the figure below, called a Necker Cube:

Figure 1 - Necker Cube

The cube consists of two squares of equal sides, one slightly above and to the right of the other such that they overlap and the sides are parallel, with straight lines connecting the corners of one to the corresponding corners of the other. At first, the figure seems to be a cube seen from above; but then it seems to be a cube seen from below, and the two alternate. What is strictly present sensationally is a bunch of lines; that we see the figure as a cube and as from above or below is due to the noetic element in the perception of the figure. As Peirce says, “a certain theory of interpretation of the figure has all the appearance of being given in perception.”17 Such interpretive elements, noeses, what Peirce calls “perceptual judgments,”18 are present and operative in all but the rarest moments of experience. Perception is always a matter of sensation plus interpretation. As James says:

‘Ideas’ about the object mingle with the awareness of its mere sensible presence, we name it, class it, compare it, utter propositions concerning it . . . . In general, this higher consciousness about things is called Perception, the mere inarticulate feeling of their presence is Sensation . . . .19

By virtue of the noetic element in perception (and in other modes of experience, such as imagination, conception, memory, anticipation, etc.) ones does not have bare sensations but perceptions of something. When one drives one’s car, one experiences not simply a series of changing shapes, colors, pressures, etc., but the car itself – that is, one takes a changing series of sensations to be perceptions of a single intentional object. Thus, percepts as well as concepts are intentional, they have reference to something beyond or more than what is immediately present in any single moment of experience. Just as in conception, the intentional aspect of perception is found in the fringe, the mass of indistinct feeling that tells one what it is that one is perceiving and which includes typical knowledge of what to do with it as well as incipient impulsions to perform the typical actions appropriate to it. Thus, just as in conception, the intentional aspect of perception consists in that one is oriented to action regarding its intentional objects. The function of the noetic elements in experience is the same as the function of concepts; by virtue of noeses one perceives an orderly and coherent world and is oriented to action regarding it.

Both conceptual beliefs and percepts may be true or false. This is clear in the case of beliefs; one may easily have a false idea of what a computer can do, for instance, or of the chemical properties of some substance. It is also true of percepts. Here is an experience I have had. I am looking for my pen. I glance around the desk, the bed, the dresser, etc., and do not see it. Then I look again at the desk and see the pen next to a pile of books. Clearly my first perception of the desk was mistaken; the pen was there all along but I didn’t notice it the first time. My later perception corrects the earlier.

Beliefs merge imperceptibly into noeses; what one believes to be true of the world or some aspect thereof influences one’s perception of it. The classic example is the rope that appears to be a snake. Another example: If one believes women to be stupid and docile, then one tends to see them that way, to notice when they act stupid and docile and not notice when they exhibit intelligence or strength of spirit. It is often the case that unexpected perceptions force us to revise our beliefs about the world; but it is also the case that revising our beliefs can cause us to perceive the world differently.

It is clear that noeses are integral elements of the self, because they have an influence throughout one’s experience. Noeses function automatically, for the most part; they are analogous to one’s heart and lungs in that one has little deliberate control over them, but they are constantly present and functioning nevertheless. If they were different or absent altogether (as, we can surmise, in the experience of a new-born infant) one would be different. One’s noeses are thus fundamental elements of one’s self.

I term “feeling” all that is immediately present in experience, although clearly feelings can be differentiated according to qualities and according to their different functions. I categorize feelings into five types:

The bedrock of perception is sensation; without sensation there would be nothing for noeses to interpret and thus no perception. Similarly, the bedrock of conception is the material qualities of thoughts; were nothing present to mind, one would not be thinking at all.

Feelings as they first come to one’s attention are sheer material qualities, immediately and directly there for one to be aware of. But they are also modes or ways of being aware of something else, they are media through which one is aware of intentional objects. This is obvious in the case of sensations which are elements in external perception; usually one pays no attention to the specific qualities of one’s sensations, but only to the intentional objects.

I distinguish bodily sensations from sensation in general because it is often the case that they seem to be intermediary between the one who perceives and the intentional object perceived. This is clearly the case with respect to touch. When one touches a table one feels the table, of course, but also one’s fingers. When one smells one smells something – tobacco or perfume or something one does not recognize; one does not just experience states of one’s nose. This medium-like quality of bodily sensations is least clear in the case of sight; one chiefly pays attention to the intentional objects that one sees, not the sensations which are elements in the perception of them, and even when one does, as when enjoying a beautiful sunset, one experiences them more as aesthetic objects than media. I think it reasonable to suggest, on the analogy of the other sense-modes, that visual sensations be regarded as feelings of the eyes, just as tactile sensations and smells are feelings of the skin and nose. Of course, one sometimes experiences one’s body directly, as when enjoying the feeling of a full stomach after dinner or having a headache. But even then one’s bodily sensations are localized to some extent; when one has a headache, the ache is a state of one’s head, which can be regarded as the intentional object of an introspective perception of which the ache is the sensational element.

Other feelings have this same medium-like quality, a state of affairs I express by the Principle of Correlativity: a feeling arises correlatively to the intentional object of which one is aware. With respect to emotions, one does not feel admiration, awe, respect, disdain, etc., simply as vaguely directed feelings; they are ways of being aware of and in relation to something particular beyond themselves – in the cases mentioned, usually people. Moods, too, pervasive feelings of contentment or unhappiness, eagerness or lethargy, for instance, arise correlatively to an intentional state of affairs, which is just as pervasive – one’s world in general or the situation one finds oneself in, not any single thing but the broad character of all or most of what one is aware of and in relation to.

The final category of feeling is impulsion to action. Impulsions are like “least actions” or incipient actions. They are feelings of almost initiating an action and are noticeable chiefly when one nearly starts to do something but hesitates, like stopping oneself from reaching for another cigarette. Were they actualized they would issue in full action, the intentional object of which would then occupy one’s attention and not the feeling of acting. Impulsions also arise correlatively to intentional objects, as do other types of feeling, but they are distinguished by being media in a double sense. They arise correlatively to something experienced, but also to something (almost, at least) acted upon. If we regard experiencing as a somewhat passive process (although there is a lot of activity going on in the noetic functioning and in active paying of attention), then acting is the opposite, and impulsions to action are media in both processes.

Feelings are not clearly differentiated, even though one can reflectively distinguish different types. They pervade and interfuse each other. All feelings have some component of impulsion to action; feelings call for expression, for action. All feelings include some tendency to become manifest outwardly by means of voluntary or involuntary bodily action. This is true on all levels, though the less intense the feeling, the less overt and immediate will be its expression. Only when an exceptionally intense sensation strikes one, a loud noise, perhaps, or a sudden pain, is one likely to react right away, by turning one’s head or saying “Ouch!”

Ordinarily sensations provoke at most mental contemplation of what to do with the intentional object of the perception or continuation of the course of action in which one is already engaged. On the other end of the scale, moods affect the over-all character of how one acts though they do not provoke any particular action. One’s depression or elation or boredom or interest, etc., is expressed in the general way one conducts oneself.

Emotions, too, call for expression. It is useful to pay particular attention to emotions because their characteristics are like those both of sensations and moods, though not quite so extreme. They arise correlatively to intentional objects as do sensations and moods (in sensation we pay attention chiefly to the intentional object; in moods, to the feeling); and they call for expression in action (sensations, as elements in perception, provoke particular actions; moods provoke over-all styles of action). By saying that they call for expression, I mean that whenever one has an emotion one has some urge to make it manifest outwardly by means of voluntary or involuntary bodily action, or facial expression, or talking about it, or tone of voice or gesture, etc., or perhaps some longer-range course of action. The term “expression” includes the following:

Emotions are primarily (but not exclusively) media through which one is conscious of other people, and much of the action they provoke is expression to others. For instance, when we like someone, the liking is an emotion, and it provokes us to smile at that person, to pay attention to him or her, to help that person out or do something nice for him or her.

The function of feelings to be media, both experientially and actionally, is something automatic, something that goes on whether one wants it to or not. But one can by one’s deliberate actions either facilitate or interfere with this function. If one is angry, for instance, one inadvertently expresses the anger in an abrupt way of speaking, a tense and agitated style of movements, etc., but one can also try to hide the anger, deny it expression, and pretend not to be angry. Or, one can express the anger directly by speaking harshly to the person with whom one is angry or by telling that person that one is angry and why. Or, one can go to a disinterested third party and release the anger through physical discharge. In this example, anger is in part the medium through which one is conscious of the person, and one can either try to deny it or pay full attention to the feeling and what specifically (or generally) is provoking it. There is a functional correlation between emotions as experiential media and as actional media. The more one is in the habit of being conscious of one’s emotions, the more one can choose how to express them. The reverse is also true: it is often the case that we notice what we are feeling in the act of expressing it.

Inhibition of the natural functioning of feeling leads to frustration and unhappiness. When one does not express an emotion and, correlatively, does not become conscious of it to any great degree, it is not the case that the emotion is not present. It is, but one is not paying attention to it. The drive toward expression does not go away, but is channeled elsewhere, perhaps into feelings of anxiety or disgruntlement. It is as if the energy that should have been expressed gets contained and goes sour.

Unexpressed emotions inhibit one’s ability to think clearly and act purposively. Painful emotions such as grief, sorrow, fear, anger and boredom require release or discharge in the form of crying, trembling, vigorous raging and interested talking. When they are denied that release, the result is a continued state of pain (whether or not one pays attention to it) and rigid patterns of thinking and behaviour. Discharging the painful emotion has a cathartic effect. One is freed from the pain and has more free attention to devote to thinking and acting effectively. With respect to the immediate contents of one’s experience, discharge drains the emotion, makes it go away or reduces its intensity. With respect to one’s on-going experience, discharge reduces the frequency of occurrence of the painful emotion and the intensity of each occurrence.20

When one expresses emotions directly and fully, one experiences, not frustration, but a pleasant feeling of being in tune with oneself. Deliberate channeling of emotions into full expression promotes an over-all feeling of well-being, just as inhibition of their natural functioning promotes unpleasant feelings of frustration and rigid and unhelpful patterns of thinking and acting.

Finally, let me note that nothing is devoid of emotion. In all of one’s perception, imagination, recollection, thinking and action there is, at least to some minimal extent, emotion present. This is another way of saying that everything one experiences is experienced valuatively, as, at least, attractive or repellent. As such, there is some (at least) incipient impulsion to action involved in all experience, though it be largely latent, as in perception, or unparticularized, as in moods. One always experiences some urge to express oneself.

The degree of effect of feelings is a function of their intensity, duration and frequency. A pervasive mood is not very intense, but influences the style of one’s action over a long period of time; a sudden flash of anger immediately alters the course of one’s action, even though it be gone a short while later. A chronic or habitual feeling that arises again and again influences the course of one’s life. In the long run, feelings that are allowed expression have more beneficial influence than ones that are not, for the capacity to feel and express atrophies without actualization. Fleeting and mild feelings have little effect on one’s action; they merely belong to one, but do not make up one’s self. Intense feelings, pervasive bodily and emotional feelings and moods, frequently repeated feelings, and feelings that are allowed expression most fully constitute one’s self.

There is another element of the self which is not present in every moment of experience but which one recognizes, when it is present, as being an integral and intimate element in who one is: the self-concept, one’s idea of who one is. It is, in part, a concept like other concepts, distinguished only by being a concept of oneself rather than any of the other intentional objects. It is also highly emotional and valuational. It is by means of the self-concept that one evaluates oneself, one’s actions, attitudes, emotional responses, beliefs, etc.

The function of the self-concept is three-fold. It is the conceptual filter through which one is conscious of oneself, it governs one’s habitual routine action, and it makes possible the self-transcendence which is at the root of human freedom.

The self-concept is obviously the means by which one thinks about oneself. It also plays a part in immediate perception of oneself. Beliefs merge imperceptibly into noeses, and as the noetic element in self-perception the self-concept governs what aspects of oneself one can and cannot be conscious of. Thus, the self-concept tends to be self-validating, since one’s perceptions of oneself reinforce it. If one’s self-concept is mistaken, however, it can be corrected. New experiences can revise one’s image of oneself, others can tell one things about oneself that one has overlooked, and one can practice a kind of epoché with regard to oneself in order to see just how the self-concept is functioning in perception of oneself.

One’s self-concept governs one’s habitual and routine action. Part of the knowledge included in the self-concept is knowledge of what to do in a vast range of typical situations, i.e., situations that recur and of which one has a stock of knowledge at hand, as Schutz says.21 Note that an incorrect self-concept distorts perception of oneself; this can result in actions that are inappropriate to a situation and do not achieve their goal, or otherwise end up in frustration and unhappiness. The usefulness of having a correct self-concept is evident.

The self-concept is the means by which one can transcend and create oneself. If you want to improve or change yourself, first you must have some notion of who or what you are. By virtue of having a concept of yourself your can compare yourself to envisaged possibilities of who you might be. If you are timid by nature, you can notice that, form a concept of it, and compare it with other possibilities, such as being more assertive. In such comparisons we can evaluate ourselves and decide to keep on acting the same way or to change, and then go ahead and do what we have decided. Thus, one creates oneself (at least in part); one exerts a deliberate influence on one’s future or present actions. One transcends oneself in that one always has the possibility of being more, or at least other than, what one currently is. One can envision one’s possibilities and, within the limits imposed by physical nature and habit, actualize them. The self-concept enables one to do so; that is, its function is to orient one to action regarding oneself. As is the case with all concepts, its intentional aspect is its function.

There is one more element of the self which is present in experience at all times. It is the self-sense, a quite global, undifferentiated and pervasive feeling of oneself, a feeling of being “me”. James alludes to it: “The basis of our personality . . . is that feeling of our vitality which, because it is perpetually present, remains in the background of our consciousness.”22 It is the result of the confluence of all the other elements of the self, one’s bodily feelings, one’s moods and emotions, beliefs, evaluations of oneself, and the feelings concomitant with one’s actions. It is what gives one a feeling of continuity, extending far into the past; is what lets one know, without thinking about it, when one gets up in the morning that one is the same person who went to sleep here last night. It is present continuously, though most often unnoticed, in all one’s unreflective experience and most of one’s reflective experience.

Each of us is always active, but action is hard to grasp phenomenologically. One can pay attention to an experienceable manifestation of the other aspects of the self, some material quality, as well as the functions they perform. But when one is acting, one’s attention is focused on the intentional objects that one is acting on, toward, or with. The degree of attention in the original experience governs the degree of retention immediately and subsequently afterwards; if one was not at all conscious of the fringe of one’s experience when one was engaged in some action, then one does not retain it or remember it. It was only upon recognition of this fact that I myself became able to disengage myself from my action as I was performing it or immediately afterwards in order reflectively to apprehend the whole of my experience of the action. Since I have become able to do that, and aided by reflection upon myself in the modes, “remembering myself” and “thinking about myself,” I have discovered that there are different types of action and different sets of subjective and noetic elements invariantly present in the experience of each.

One can become conscious of one’s acting, if not I-the-actor, by being conscious of one’s impulsions to action, the envisioned goal, if any, of one’s action, and the specific perceptual judgments and bodily and emotional feelings that occur concomitantly and correlatively to what one is aware of and acting toward, on, with, etc. One is also aware of one’s acting by being aware of the broad moods and emotions that arise correlatively to it over longer periods of time.

There are two main types of action, each with its typical concomitant emotional-interpretive complex: deliberate action and habitual action. Most of one’s action is neither purely one nor the other, but it is useful to abstract these two extremes as ideal types.

Deliberate action is action that one envisions or plans beforehand, decides to do, and then does according to one’s plan. Its distinctive feature is, as the name implies, that one deliberates, thinks about what one is about to do. One’s attention is split or oscillates between what is before one and one’s plan. Concomitant to this split between the actual and the ideal (mentally envisioned), there arises a sense of agency, a sense of I-doing.23 This sense arises also when one is in the process of making a decision, in which one’s attention is split up between two or more envisioned possibilities of what one might do. The sense of agency arises upon reflective apprehension of oneself as agent, when one thinks about what one is going to do or is doing or when one’s action is inhibited because one has not yet made up one’s mind. When one is unreflectively and straightforwardly acting, one’s attention is directed toward the intentional objects of the action; the self-sense and any dim sense of agency are present only marginally, unnoticed.

Most of one’s action is not completely deliberate or thought out, but in all but the most unthinking, routine, habitual action there is some dim glimmering of the sense of agency. James says that “a good third of our psychic life consists in . . . rapid premonitory perspective views of schemes of thought not yet articulate,”24 a statement I would amend to include schemes of action not yet articulate as well. The more fully such a sense of I-intend-to-do-such-and-such is present, the more deliberate is the action, and the more there is a sense of agency. It is by means of the sense of agency that one apprehends certain of one’s actions as one’s deliberate doing.

If the sense of agency is absent altogether when one is doing something, then one’s action is either ecstatic or habitual. Ecstatic action occurs when one is doing something one has not done before but has no idea, no premonition, of what one is doing. Spontaneously making a joke or improvising music are examples. Habitual action occurs in the form of typical routines that one performs over and over again. One gives no thought to what one is doing; the action performs itself, as it were, automatically. There is no sense of agency, and the action can be said to be one’s own only because it is oneself and not someone else who does it. In the most extreme cases, one need not even pay much attention to the intentional objects of the action; when I brush my teeth and wash my face in the morning, my thoughts are usually entirely elsewhere. It is a fundamental characteristic of the self to form habits; every action is, if not already habitual, at least incipiently the beginning of a habit, for one experiences an impulsion to repeat everything one does unless something else intervenes, such as frustration or the intention to do something else.

Most of one’s everyday action is neither purely deliberate nor purely habitual, but consists of typical routines that are complicated enough to require some thought, but not so unfamiliar as to require full deliberation and rational planning. Cooking dinner, buying a book, taking notes in class are examples. Such courses of action are habit-like in that they are typical routines that one performs again and again and does not have to think much about. They are somewhat deliberate in that there is present in one’s experience of doing them some idea of what one is doing and why, some glimmering at least of a sense of agency.

I use the term “attitude” to refer to the inner, thinking and feeling, side of habitual and routine or semi-routine action. An attitude is a complex of feelings, interpretations, and action-schemata directed toward an object such that one perceives the object valuatively interpreted and is impelled to act in a certain way regarding it. Attitudes include intentions (in the ordinary sense) with respect to one’s actions, expectations of how the object will behave, typical knowledge of its characteristics and what one can do with it, etc. Attitudes also include evaluational feelings, such as liking or disliking, approval or annoyance, etc., which find expression in typical actions or at least impulsions to action.

Habits and routine actions have a sort of inertia; the longer established and more often repeated they are, the harder they are to change. One can, nevertheless, change them, either stop doing them or do something else or alter some part of a routine, and this in two ways. One can change one’s attitudes or one can change one’s actions, and a change in one invariably leads to a change in the other, for they are the inside and outside of the same thing.

In order to change a habit, in either of these ways, one must exert an effort of will; if not, the habit will continue out of its own inertia. As James points out, the crucial element in exerting an effort of will is being always conscious of the idea of what one wants to do.25 If one forgets to think of changing a habit, it will automatically reassert itself and take over. Clearly, exerting an effort of will is a kind of deliberate action.

As with subjective processes generally, different attitudes and their correlative routine action-patterns may be more or less influential elements of the self, and the marks of their influence are duration, intensity and frequency. Trivial attitude-habits like not liking eggplant have only a slight effect on one’s experience and action. The most influential attitude-habits are the most pervasive, like being eagerly interested in life or cautious and afraid of it, and the most intense, such as severe claustrophobia.

All of the elements of the self function teleologically, as if oriented to a goal; they all contribute in one way or another to one’s experience and action. One’s beliefs and noeses structure one’s experience and guide and channel one’s action. To know what something is and to perceive it as what it is, is to know what to do with it. One’s feelings are the bedrock of experience. If there were nothing immediately there to be aware of, one would neither experience nor act, but only behave, like an inanimate thing (ignoring for the moment the metaphysical assertion that everything, in some way, experiences). One’s emotions and moods are media through which one is conscious of particular objects, especially people, and one’s world or situation as a whole. One’s emotions provide the immediate motivational force for action, and one’s moods determine the overall style of one’s action from day to day. One’s self-concept is one of the most fundamental and all-pervasive beliefs and is a strong conditioning factor in self-perception; the valuative thoughts and feelings about oneself that arise from the self-concept are prime determinants in the way one acts. One’s attitudes, being combinations of belief, emotion, and impulsion to action, structure one’s experience and both motivate and channel action. They are the inside of habits, habits as subjectively experienced. One’s deliberate actions begin habits and are based on one’s perceptions, beliefs, emotions and valuations of oneself and one’s world.

The self has a basic teleological structure, and it is but a flip of the coin whether we call the goal experience or action. Ortega says action: “Man’s destiny . . . is primarily action. We do not live to think, but the other way round . . . .”26 But one’s action itself has a goal, which is two-fold. First, the goal is preservation of oneself; one’s action basically functions to keep one alive and functioning. Second, the goal is to feel good; one acts to achieve satisfaction. Of course this goal is founded on the first in that one must be alive in order to feel anything. Whitehead states it succinctly: “. . . the art of life is first to be alive, secondly to be alive in a satisfactory way, and thirdly to acquire an increase in satisfaction.”27

If we forget that experience and action are inseparable, an ambiguity arises. The teleological structure of the self is to be oriented to action. But now we see that, in a sense, the goal of action is feeling, that is, feeling satisfaction. The apparent vicious circle is mitigated only slightly by noting that whenever one feels good, an impulse arises to continue feeling good, that is, to continue or repeat the actions that resulted in feeling good. It is allayed even more, however, by remembering fundamental Socratic doctrine, that a person is made happy by performing well the function that is peculiarly his or hers. Now, the most fundamental character of the self is that it is aware and acting; cessation of experience and action is death. To put the matter in Socratic terms, the fundamental function of a person, that which by nature he or she does and must do, is to experience and act. Thus, that the goal of the confluence of the elements of the self is action in no way vitiates the claim that the goal of action is a kind of experience, satisfaction. On the contrary, the two are strictly correlative; it is a natural result of the structure of the self that acting well is accompanied by the experience of feeling good, what the Greeks called eudaimonia, that performance of the proper functions of the self is its fulfillment.

Husserl, Edmund. Cartesian Meditations. Translated by Dorion Cairns. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1960.

Husserl, Edmund. Ideas: General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology. Translated by W. R. Boyce Gibson. New York: Collier Books, 1967.

Husserl, Edmund. The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology. Translated by David Carr. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1970.

Husserl, Edmund. The Paris Lectures. Translated by Peter Koestenbaum. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1967.

James, William. Pragmatism and four essays from The Meaning of Truth. Meridian Books. New York: The World Publishing Co., 1955.

James, William. Psychology. (Briefer Course). Premier Books. Greenwich, Connecticut: Fawcett Publications, 1963.

Ortega y Gasset, Jose. Man and People. Translated by Willard R. Trask. The Norton Library. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1963.

Peirce, Charles Sanders. Charles S. Peirce: Selected Writings. Edited by Philip P. Wiener. New York: Dover Publications, 1966.

Peirce, Charles Sanders. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, Volumes V and VI. Edited by Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1965.

Re-Evaluation Counseling web site, http://www.rc.org/.

Schutz, Alfred. Collected Papers I: The Problem of Social Reality. Edited by Naurice Natanson. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1967.

Whitehead, Alfred North. Process and Reality. Harper Torchbooks. New York: Harper and Row, 1957.

Whitehead, Alfred North. The Function of Reason. Boston: Beacon Press, 1958.

Wikipedia, "Necker Cube" (On-line publication; URL = http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Necker_cube as of 14 April 2008.

Zaner, Richard M. The Way of Phenomenology. Pegasus Books. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Publishing Co., 1970.

|

Version |

Date |

Author |

Change |

|

1.0 |

27 July 2008 |

Bill Meacham |

First publication |

|

1.1 |

18 June 2010 |

Bill Meacham |

Minor grammatical revisions. No substantive change to content. |

1 Husserl, Ideas, p. 107

2 “Object” with a capital O is a translation of Husserl’s use of the German word Objekt as opposed to Gegenstand, translated as “object” with a lower-case O (Husserl, Cartesian Meditations, tr. Dorion Cairns, p. 3, translator’s note 2). An Object (Objekt) is public, “there for everyone,” but an object (Gegenstand) is simply something present in experience, something of which one is aware in some way. Thus an object (Gegenstand) may be public or private.

3 Husserl, Ideas, p. 200

4 Husserl, Cartesian Meditations, p. 34

5 Husserl, Ideas, p. 203

6 Husserl, Ideas, p. 203

7 Husserl, Crisis, v., for instance, pp. 142-151

8 Husserl, Ideas, pp. 96-100

9 Husserl, Cartesian Meditations, p. 35 (emphasis omitted)

10 Husserl, The Paris Lectures, tr. Peter Koestenbaum, p. 13

11 Zaner, The Way of Phenomenology, pp. 35-36; cf Husserl, Ideas, p. 259

12 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p. 245

13 James, Psychology, p. 157

14 James, Pragmatism, p. 115

15 Peirce, Selected Writings, pp. 98-99

16 Husserl, Ideas, pp. 228, 230-231

17 Peirce, Collected Papers, Vol. V, p. 114

18 Peirce, Collected Papers, Vol. V, pp. 38, 114-115

19 James, Psychology, p. 26

20 The observations in this paragraph come from the theory and practice of Re-evaluation Counseling. See http://www.rc.org/.

21 Schutz, Collected Papers I, pp. 7-8

22 James, Psychology, p. 191

23 In German, Ich-Akte. Zaner, The Way of Phenomenology, p. 138.

24 James, Psychology, p. 157

25 James, Psychology, pp. 393-394

26 Jose Ortega y Gasset, Man and People, tr. Willard R. Trask, p. 23

27 Whitehead, The Function of Reason, p. 8 (emphasis omitted)